Giving the gift of heritage

Roughly 30 million people have tested their DNA, most since the industry’s 2017 spike.

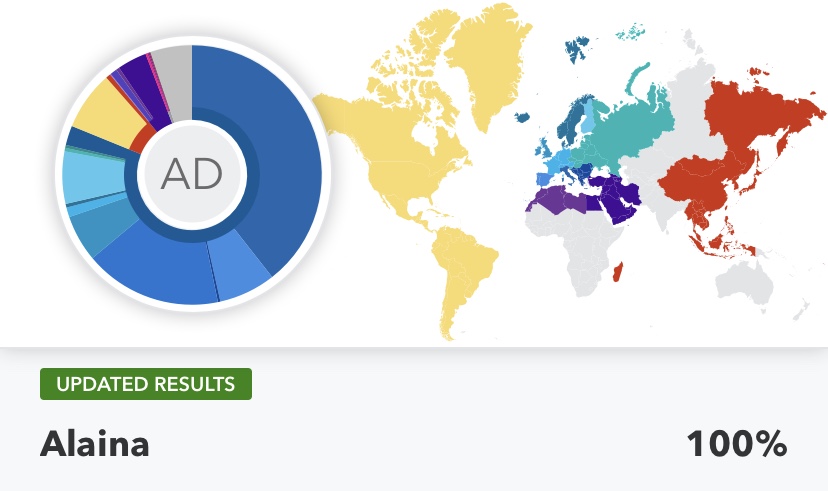

Freshman Alaina Durone’s DNA is reported through the 23andMe website. Durone is mostly Southern European. photo courtesy of Alaina Durone.

December 13, 2019

On Christmas night 2018, freshman Alaina Durone opened a present to find what she had been anticipating: a DNA test kit. It was a gift from her father and stepmother, who purchased testing kits for themselves, as well as Durone and her sister.

“[My sister] had actually mentioned them a few times and she and I both agreed that we thought it would be a really cool experience for us just to try, because everyone in our family [wa]s saying that our heritage is something else, and it seems like every other day our grandpa has some crazy story of how we’re from another country,” Durone said. “So we were like, ‘I think that we should try this,’ and we’ve always wanted to know where we’re from.”

The two companies that dominate the direct-to-consumer (as opposed to having a healthcare provider act as a middleman) genetic testing market, 23andMe and AncestryDNA, offer users an estimated percentage breakdown of their genetic ethnicity. Customers can order their kits online, provide their DNA sample in their saliva and receive their results on the company’s website. Results of the DNA test show them which regions their ancestors originated from or lived in. The company may also include information about family migrations and the buyer’s traits (for example, earlobe type and aversion to the taste of cilantro) and even medical information, a right 23andMe had temporarily taken away. For some, it provides an opportunity to feel connected to their heritage. Or it can simply be a way to easily and conveniently learn about their genetic predispositions.

Senior Emma Peck always wanted the chance to test her genetic makeup, an opportunity she finally received her freshman year when her mom bought her an AncestryDNA testing kit.

“I feel very fortunate to have been born in this century, or time period, because we do have so much technology to help like for healthcare, and we have such a better understanding of the human body,” Peck said.

Companies like AncestryDNA do multiple forms of genetic testing, using algorithms to find patterns of variation in DNA that are common among people of a certain background. The percentage of a certain ethnicity or nationality they report depends on how much of the DNA exhibits the pattern. The DNA sample is provided by the buyers like Peck in their saliva, who was eager to see her results.

“I’m adopted, and I’ve always wanted to do the test, but for the first half of my life, the tests were very expensive — they were like $1,000 to go get the DNA test done,” Peck said. “And then all of a sudden these little kits came like Target and stuff, and online.”

Both 23andMe and AncestryDNA’s most basic test kits cost $99.The industry saw a massive spike in 2017, 10 years after 23andMe came out with its DNA test. According to Business Insider, the trend has already begun to slow down and plateau, possibly in part due to concerns over privacy and ethics.

“Obviously I was skeptical about taking this test, just because I was like, ‘my saliva’s going to tell all this information about me?’” Peck said.

However, DNA testing’s popularity has also sparked other opportunities for businesses to capitalize on people’s interest in their ancestry. It has paved the way for the DNA or heritage travel industry, where companies sell cultural trip experiences in the traveler’s ancestral homelands that attempt to foster a connection with their heritage. In an Ancestry poll of 2,000 Americans, 84% of respondents said it was important to know about their heritage. The heritage industries popping up are offering to help people with this desire to know where they come from. For Durone, heritage carries a cultural significance.

“I know as a kid, I was really curious about it,” Durone said. “Because all of my friends knew exactly where they were from, like everything, whereas I just didn’t. So then I was like, ‘I want to know where I’m from,’ and I just want to be able to tell my kids and my family where I am from so then they know and then we can celebrate the little stuff.”

AncestryDNA and 23andMe’s success is partly thanks to the fact that the more customers they have, the better and more expansive the databases they can offer consumers become, allowing them to amass more and more of the market. Kate Riffel, a Kansas City resident, found her half-brother on Ancestry’s site and was able to connect with her birth father and his family, an experience that meant more to her than finding out just her DNA test results.

“Who would have guessed that trying to figure out ‘am I really all Irish?’ would lead me down this path of having a heritage I never knew I had, you know?” Riffel said.

According to her, meeting her birth father and half-brothers has been healing, especially to her birth father, in addition to giving her a sense of rootedness.

“I wouldn’t really say it was a giant wound, but it’s something that’s missing in your life when you don’t know your heritage,” Riffel said.

Heritage trips are meant to provide meaningful experience and discovery for the traveler, expanding on their DNA test results. However, biological ancestry represents different things based on the person. To Riffel, getting to see her genetic influences and familial resemblances was fascinating.

“I think life is quite a mixture of genetics and environment,” Riffel said. “So, here’s what I’m saying: I’m surprised how much genetically I have picked up in my personality from a man that I never grew up with.”

Riffel also plans to try to reach her birth mother when she becomes eligible as a New York adoptee to apply for her original birth certificate Jan. 15. On the other hand, Peck is not interested in trying to meet her birth parents. Since she was adopted from another country, she doesn’t feel her genetic heredity influences her cultural belonging.

“[My heritage] is always going to be there, but it’s not going to be a cultural part of me,” Peck said. “…But for me personally, I have no want or desire to embrace myself in [Chinese] culture, but that’s just because I grew up in the United States, not because I don’t care.”