Cultivating Consent: High schools handle sexual assault

As sexual assault becomes an increasingly acknowledged phenomenon, the Dart looks into what policies, prevention measures and discussions schools have in order to create a culture of consent.

December 11, 2017

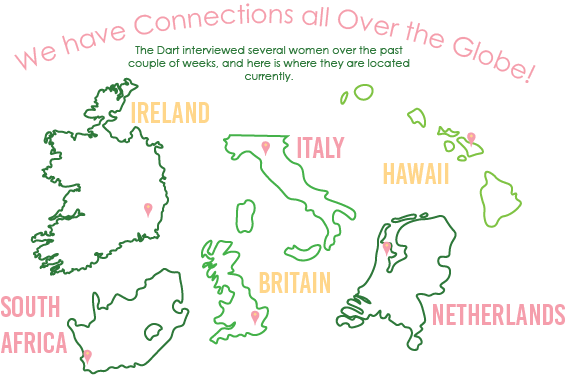

Over the past month it was impossible to open Twitter, Facebook and any other major social media site without being met by countless women and men sharing their stories of sexual harassment, assault and abuse using the hashtag #MeToo. Big names in politics and Hollywood were making headlines that included words such as “sexual harassment” and “rape allegations.”

Two summers before, America latched onto People v. Turner as Stanford student athlete, Brock Turner was sentenced to 3 months in prison after being convicted of sexual assault. This caused sexual assault on college campuses to be highlighted as a more pervasive issue than ever before. However, sexual violence is prevalent in our society far before people get to college.

According to a Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN) study, 44 percent of all sexual assaults are under 18 years of age. According to Victoria Pickering, coordinator of Education and Outreach Services at the Metropolitan Organization to Counter Sexual Assault (MOCSA), children begin encountering rape culture in society from a very young age and that even fifth graders are “expressing sentiments of victim blaming.”

While there are resources at the college level such as The Office for Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination at UC Berkeley, a Public Religion Research Institute survey of 2,000 millennials showed that over half believed “incidents of sexual assault are somewhat or very common in high schools.”

“High schools are basically where colleges were like 15 years ago — in the Dark Ages,” said Colby Bruno, senior legal counsel at the Victim Rights Law Center in an article from Al Jazeera America by Claire Gordon.

Guidance counselor Amanda Johnson Whitcomb believes that it is important to start an open dialogue about sexual violence early on in high school.

“As students starting to gain more freedom, getting their driver’s license, starting to develop serious romantic relationships, going to more social events they are being presented to a culture where instances of sexual harassment are more common,” Whitcomb said.

In order to best write policy on and start a conversation about sexual assault, it must be fully defined. By United States Department of Justice’s definition, sexual assault is “any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient.” The words “explicit consent” are a key part of this definition. According to the University of Michigan Sexual Assault Prevention and Awareness Center (UMSAPAC), to be considered explicit, consent must be freely given. It cannot be assumed through body language, appearance, or non-verbal communication and does not depend on dating relationships or previous sexual activity. In the case of intoxication, incapacitation, immobility or any other situation where a clear verbal signal can be made, consent is not valid. Additionally, consent should be withdrawable at any point in the sexual activity.

Any sexual activity outside these parameters is considered sexual assault, and rape in the case of penetration. Because sexual assault falls under sex discrimination, it is covered by Title IX, an educational amendment that states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

Pickering says that any school that receives public funding is required to have a Title IX coordinator and to have policies in place to prevent sex discrimination which also includes sexual harassment and sexual assault.

All Title IX schools are required to have an investigation protocol in place in the of instances of gender discrimination. This could be defined as anything from a schools refusing to have an equal number of boys and girls sports teams, all the way to sexual harassment or even the schools discrimination of LGBTQ students.

“The key to Title IX is making sure no one loses their access to education, and to help make sure that the victims voices are heard in that process,” Pickering said.

All teachers and administrators are “mandated reporters,” and are required to report any instances of sexual harassment, assault and abuse to local authorities. Whitcomb says that if a student comes forward with a case of sexual harassment or assault she would report the case to parents, the local authorities and then refer the student to MOCSA.

While STA is not legally mandated to use Title IX because it is a privately funded institution, they use the premise of it in their policies and provide MOCSA training, along with a diocesan program called “Protecting God’s Children” and self defense courses. Programs have been specifically chosen to improve awareness and teach defense tactics for students’ time in high school and beyond.

In order to prevent sexual assault from happening in the first place, the culture that supports it must be questioned. Pickering defines rape culture as “a culture in which sexual violence is both expected and accepted,” It can manifest itself at the high school level through sexually explicit jokes, gender roles that expect dominance from men and submission from women, pressure on men to “score” sexually, assuming that men don’t get raped and blaming the victim for their assault, according to UMSAPAC. Principal of Student Affairs Liz Baker sees another example of rape culture at the highschool level during school dances, where groping is an issue.

“Some people just don’t know where the boundaries lie, it’s very quick but it is so much a violation of privacy,” Baker said.

The Kansas City Public Schools’ handbook touches on many of these elements of rape culture. It defines sexual harassment as “inappropriate or unwelcome behavior, or verbal, written or symbolic language which creates a hostile environment, including sexual threats, sexual proposals, sexually suggestive language and/or gestures and unwanted physical contact based on gender or of a sexual nature.” Any of these actions are requested to be reported to an administrator or staff member.

Whitcomb believes that these ideas develop in adolescence, and that they allow rape to become normalized and even trivialized.

“Especially with young people, rape culture comes down to a lot of myths about rape and sexual assault in that people are not aware or knowledgeable about what it truly encompasses,” Witcomb said.

According to Chris Bosco, Assistant Principal for Student Life at Rockhurst High School, Rockhurst uses assemblies with MOCSA to perpetuate a discussion of why sexual violence is never okay.

Will Tampke, student body president of Rockhurst High School, has sat through a couple of assemblies on sexual assault, but questions how effective it is to sit students down and simply tell them not to sexually assault other people. While he believes it is important for Rockhurst administration to make a statement that sexual assault is not acceptable, he sees the most change being made through everyday conversations and interactions with others.

“If it isn’t okay to say something if a girl is in the room, it shouldn’t be okay if she isn’t,” Tampke said.

When he does hear statements that perpetuate rape culture, Tampke believes it is important to encourage reform instead of demonizing the person or automatically labeling them as a misogynist. He believes that once people realize what impact their casual words and jokes about sexual violence could have, they might be encouraged to stop.

“You can’t make a rape joke because you can’t say the idea of rape is funny,” Tampke said.

Whitcomb believes that because the majority of sexual assault victims are women, it is vital for sexual assault and harassment to be included in school discussions. By starting this conversation in the classroom, teachers can amend some of these stigmas. They can create a culture of consent and support for those who have experienced assault before or during high school.

Librarian Carrie Jacquin made a point of covering issues concerning women, including sexual assault, in her curriculum as a freshman english teacher. She kept in mind that her students were just entering the world of dating and was also motivated by the statistic that 1 in 5 women will be sexually assaulted in the course of her life.

“It’s something that I think [teachers] have a duty to inform [students] about and try to raise your awareness about so you can protect yourselves,” Jacquin said.

Students in Jacquin’s classes had the option to choose sexual assault as their final research paper topic. Current junior Ann Leverich wrote her paper on the underreporting of sexual assaults on college campuses. When a close friend of hers was assaulted by someone they knew, she realized how important it was to clear up the misconception that rapists are strangers, as 80 percent of all rapists know their victim, according to MOCSA.

“I think it’s important for more education on the topic for women to know it’s not their fault, because society tends to blame the women in those situations,” Leverich said.

Last year during junior-senior service week the underclassmen attended a Women’s Symposium, organized by Jacquin, on one day in place of regular classes. Students went to several presentations on social issues, especially those that apply to women. Leverich saw this as a chance to inform younger students as they enter high school and hopes it is continued in the future. She also notes how useful it is to have gone through self defense training at one of her sophomore class meetings.

“You have to be able to defend yourself in tough situations, you don’t want anything to go too far,” Leverich said.

Before juniors and seniors go out for their service weeks, they are required to attend a “Protecting God’s Children” session that informs them how to spot signs of sexual abuse in children. This is a program offered by VIRTUS, created by the Catholic Risk Retention Group.

“We always want [students] to be safe wherever you may be working, so education is going to lead to better awareness,” McKee said. “The more aware you are of what to look out for, ultimately the safer you will be.”

Sophomore year at STA, students attend a teen exchange program presented by MOCSA where they are allowed to freely ask questions about sexual violence. Tampke has attended one such event downtown, and tried to bring what he learned back to his peers at Rockhurst.

“[‘No means no’] really should be ‘yes means yes,’” Tampke said. “The absence of a no doesn’t necessarily mean a yes.”

Pickering says that while the content of the presentations is the same no matter the gender of the crowd, it is the discussion afterward that differs. A RAINN study showed that women ages 16-19 are four times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape or sexual assault. Because of this, the post-presentation conversations with women tend to be more naturally flowing.

“Although we do know that sexual violence can be committed by someone of any gender and experienced by someone of any gender, gender does play a big part,” Pickering said.

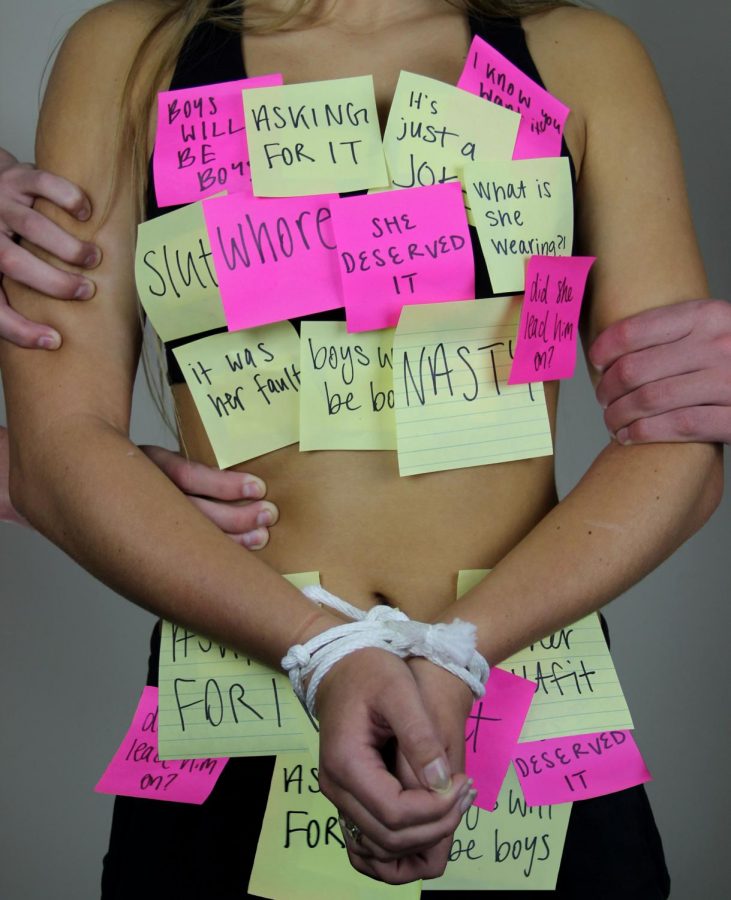

According to RAINN, two out of three sexual assaults go unreported, making it the most underreported crime in the nation. RAINN attributes this to victim blaming, fear of reprisal, slut shaming and social stigmas about the nature of assault that keep victims in silence. The same qualities that embed our society with a rape culture keep victims silent, so that 99.4 percent of perpetrators are able to walk free.

Baker hopes that by providing students and teachers with training through MOCSA and having a set procedure for if a student comes forward with sexual assault, harassment or abuse that provides them with a sensitive intake and assessment will provide safety and understanding on campus.

“The number one thing for everyone to know about sexual assault is that it’s never a victim’s fault,” Pickering said. “No one has the right to do anything with you without your consent.”