The Enormity of A Little Life

Hanya Yanagihara’s “A Little Life” is made by its characters. It is destroyed by its use of excessive, graphic trauma to keep the reader from looking away.

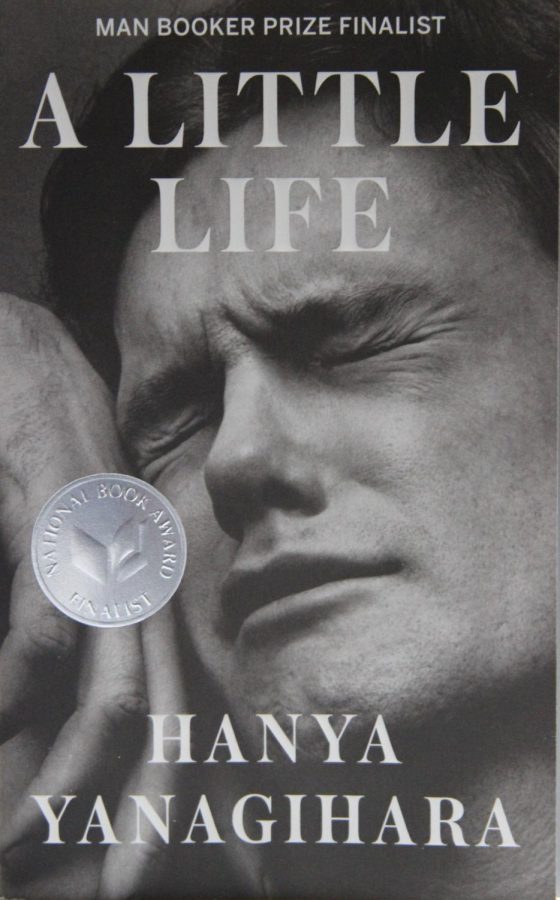

photo by Grace Ashley

August 30, 2020

I first heard about Hanya Yanagihara’s “A Little Life” on Youtube. It was the beginning of quarantine and I was looking for something new to read, and this book kept coming up again and again. I had heard a lot of mixed reviews on it; some called it pretentious and wordy, others called it a modern classic, and some others called it emotionally manipulative and destructive. So, naturally, I ordered it on Amazon and began to mentally prepare myself to read it. In the end, I read it twice, and the second experience was just as miserable as the first.

Before I get too into this, I want to say that I have never read anything even remotely like this. I tend to stick to plot-heavy, YA novels with characters my age that I can relate to, but “A Little Life” is the complete opposite. It revolves around the lives and friendship of four men—JB, Malcolm, Willem, and Jude—from the time they are in college to the time when their friendship ends. That’s it. There is no discernible plot throughout the 800-ish pages other than that; however, what made me pick up this book was the attachment that people expressed to the characters and how emotional the book made them. The way that reviewers talked about the characters made it seem like they were real people that they loved and cried over. And a lot of people seemed to be crying. I knew that this book was extremely emotional, especially after watching one YouTuber’s reaction to the ending (hint: she cried violently). I wanted to know, first, how people could get so attached to the characters, and, second, what happened that was so bad. I was immensely curious going in, and after two weeks of mental prep I thought I was ready.

Spoiler alert! I was not.

This is probably the best book I have ever read from a technical standpoint. The characters are so well-written that they feel tangible. It doesn’t matter if you look at Willem, with his “Scarlet Ibis”-esque origins; JB, with his narcissistic downfall; Malcolm, with his identity crises; or Jude, with his merciless self-loathing. They feel real. The relationships between the characters are incredibly dynamic and deep-rooted, both in terms of friendship and romance. I felt the pain and embarrassment Jude felt when Malcolm mocked him, the grief Harold felt as Jude slowly broke down in front of him, the warmth Willem felt when listening to Jude tell him stories. I could see JB’s paintings come to life in my mind as if I was at one of his art shows. I felt like I was there the whole time, and, while that is an incredible feat on the part of Hanya Yanagihara, it was not always a positive experience. I was just as present for the tragedies and endless traumas that fell on Jude, and I can’t help but feel that they were too much.

The fact of the matter is, this book, while beautifully written and powerfully characterized, is fundamentally problematic. I did become extremely attached to the characters and I fell in love with the writing and the relationships portrayed, but what I absolutely can’t forgive is Yanagihara using excessive trauma to make sure the reader doesn’t look away, especially when it comes to Jude. At the beginning of the book, Jude was a complete mystery even to his closest friends; however, as I kept reading, his story unfolded into a never-ending maelstrom of misery. He seemed to be given happiness only to have it ripped from him, and the severity of the trauma inflicted upon him was unnecessary and utterly disgusting to me. Looking through the book, it is easy to see that everything is written in extremes: the successes of the characters, the relationships, and, most notably, the trauma. But, the thing is, trauma is not a literary device for authors to use for shock factor. To abuse it in the way that it was used in “A Little Life” seems to cheapen the experiences of those who do live with the effects of their trauma, and it nearly ruins the book for me.

Overall, the book is a terrible masterpiece. After all of this, you may be wondering why I read this book twice. The answer is simply that I couldn’t stop thinking about it. It consumed my every waking thought for two months until I finally picked it up again. I did not enjoy it either time, even with the positives the book offers. By the end of both reads, I was sobbing hysterically. I wish I could say that I recommend this book. The writing and characterization are incredible, but the way excessive trauma is used as a hook for readers is sickening. Because of this, I would rate “A Little Life” as 2.5/5 stars.

In case you decide to pick this book up anyway, please note the following trigger warnings: rape, sexual abuse, child sexual abuse, kidnapping/imprisonment, self-harm, suicide, loss of a loved one, addiction, physical and verbal abuse, gaslighting, and verbal abuse of the disabled

B • Aug 1, 2021 at 1:06 pm

Hey, wasn’t it JB who mocked & humiliated Jude & not Malcolm?