STA’s Land History

The complete narrative of how Mother Superior Evelyn O'Neill brought us to the Windmoor campus and the legacy J.C. Nichols planned for our land.

November 27, 2018

The first thing the Sisters of St. Joseph possessed upon their arrival in Kansas City in 1866, Sister Francis Joseph Ivory recalls, was a cow. Ivory arrived by train on an advance team to raise funds to furnish what would become the convent and school in Quality Hill, a neighborhood that sat at the highest point in Kansas City. It was there that the sisters taught art, French, math, English and anything else necessary to a young woman’s education in post Civil War Missouri.

On the St. Teresa’s website, it reads: “In 1866 at 12th and Washington Streets in Kansas City’s Quality Hill district, the Academy rapidly grew in enrollment and prestige. By 1909, the Sisters relocated the school to a twenty-acre site at 5600 Main—our current location.”

Why did the sisters decide to leave Quality Hill, and how did they end up at the current location in the Plaza Countryside neighborhood? To guide our way through the history of St. Teresa’s and the surrounding areas, the Dart will be using excerpts from Mother Superior Evelyn O’Neill’s memoir “Who is Like God?” where she chronicles the move to the Windmoor location we know today.

“I was glad to be free to push the disposal of the dear old home in favor of going out farther from city traffic…[Bishop John J. Hogan] was irate at the bare mention of such procedure. My one desire was to see this school, which had known my presence all of thirty years, placed where it should be in Kansas City. But my heart sank to zero when Reverend Mother told me: ‘There is no use! You might as well give up the idea of a new building and a new site. I’ll never go near him again.’”

As real-estate development ventures began in Kansas City, Quality Hill became home to an increasing amount of businesses—by 1889, the Kansas City Merchants’ Exchange, the Coates Opera House and the Franklin School were just down the block. Private entities were buying property on the hill, and to the west, the Stockyard District began developing an area for farmers to buy and sell cattle.

The sisters felt that it was time to move out from their brick building in Quality Hill and into a new location and approached Hogan to begin the search.

Despite the Bishop’s protests due to miscommunication over who owned the Quality Hill school — the sisters or the diocese — the sisters persisted and were permitted to begin their search for new land for the school. In the second deed signed by Archbishop Peter Richard Kenrick for the school’s location in 1867, it was declared that “present purpose being to enable the good Sisters of St. Joseph to establish another school that may be more advantageously situated within the corporate limits of Kansas City.”

During the same time that the sisters were scouting out new sites, real estate developers and politicians began advertising to “scared whites,” telling them their neighborhoods would be “safe from undesirables,” according to “Racism in Kansas City,” a short history book by G.S. Griffin. As Kansas City’s black population grew, the white population moved their schools and homes further away in a phenomenon known as white flight. As a result, the Country Club and Brookside areas developed greatly between 1900 and 1920.

“Putting St. Joseph, our man of the house, in my pocket, we started to find a salable place. The old Buckley home, a good-looking brick house, faced us as we went down Jefferson Street. We rang and learned that it rented for $75 per month, and that the owner, Mr. J.C. Nichols, would be glad to sell it.”

Real-estate developer, J.C. Nichols’ objective was to “develop whole residential neighborhoods that would attract an element of people who desired a better way of life,” according to the Nichols Company records. But Nichols had a specific vision in mind for both the “element” of people he wanted in his neighborhoods and the sort of life they would lead. According to Griffin’s book, Nichols crafted elite neighborhoods in which membership in the neighborhood association was mandatory, legally requiring homeowners to enforce racial restrictions—“homes could not be sold to minorities.”

Nichols himself confirms this in an article printed in the National Real Estate Journal in February of 1939.

“For the first time in the United States, so far as we know, a plan was evolved by which restrictions automatically extended themselves at the end of the original restrictive period,” Nichols writes, directly referencing the restrictive racial covenants of his neighborhoods.

English teacher Stephen Himes explains that these restrictions are not a thing of the past.

“[Nichols] created a system in which the racial covenant would be extended in perpetuity into the future unless it was explicitly rescinded by the neighborhood association,” Himes said.

That way, Nichols neighborhoods would stay white unless its residents struck down the covenant on his terms.

“J.C. Nichols basically perfected [this] practice and, [became] a national figure in real estate circles and then exported it all over the country,” Himes said.

“Now free to act in the matter of a new school, we did some earnest praying and careful considering of many a site, and at length decided upon our present location at Windmoor. It was a moor indeed, windy and bleak and broken up by an elevating ridge running obliquely across its south half, while the north half had through it a low swampy ravine—nothing encouraging about it, nothing attractive in any way, but we had visualized it as we see it as this writing—the most beautiful school grounds in the country, a little bit of paradise.”

This moor the sisters found was land that Kate Simon Yeomans and Edwin Yeomans were eager to sell, but the two demanded payment in cash. While the Yeomans were clients of Nichols, his company had acquired so much property that it was run dry of both liquidity and credit and was unable to purchase the property, which LaDene Morton writes in her book “The Country Club District of Kansas City.”

St. Teresa’s reputation as a “venerable,” well-attended school and its ability to pay in cash made the school an ideal buyer for the land J.C. Nichols intended to include into his Country Club District.

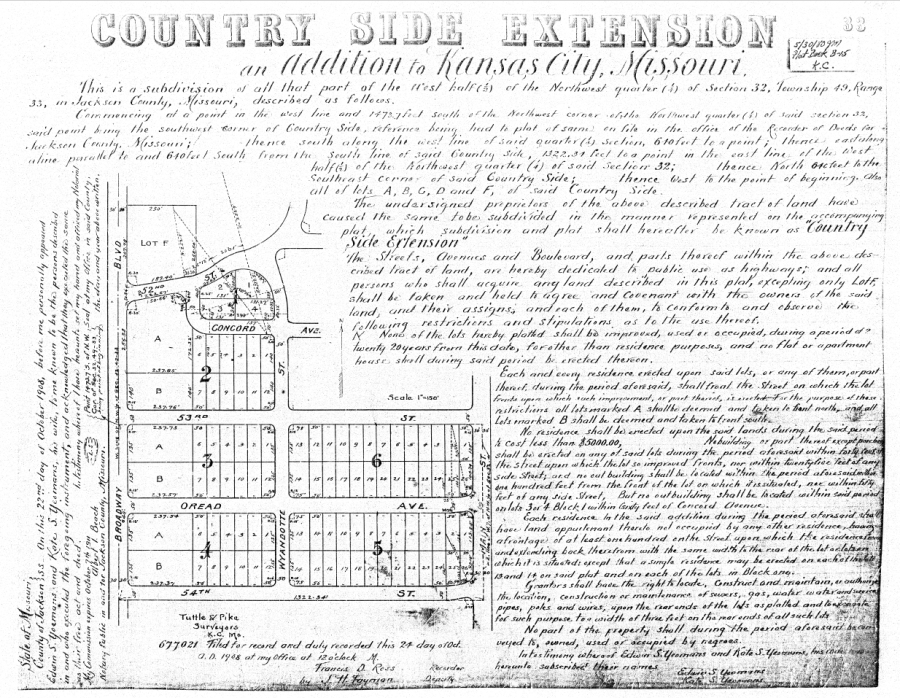

The new location was bound by 56th and 57th streets and Main and Wyandotte streets, two blocks by four blocks of land sold by the Yeomans for $40,000 consideration. This land was one of the last portions of a land parcel Nichols had prepared adjacent to the Kansas City Country Club beginning in 1905, which Sherry Lamb Schirmer writes about in her novel “A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960.” To “entice affluent buyers,” he dubbed the area the Country Club District.

The school’s move to its new location occasioned much publicity, including ads published in the Kansas City Times from the school itself that promised “NEW, SANITARY, ABSOLUTELY FIREPROOF” grounds and dormitories.

The neighborhood known as Country Side was poised to be an extension of the Country Club District. The plat of land surrounding STA was subdivided by the Yeomans in 1908, the same year the sisters acquired the land for their campus. In the text of the Country Side’s plat, Nichols’ brand of restrictions is clearly enumerated: “No part of the property shall during the period aforesaid be conveyed, owned, used or occupied by negroes.”

“Plans for the new school rapidly materialized. Ground was broken by the venerable Bishop on the Feast of St. Teresa, October 15, 1908. On account of unavoidable delays, the cornerstone of the new building was not laid until November 12, 1909.”

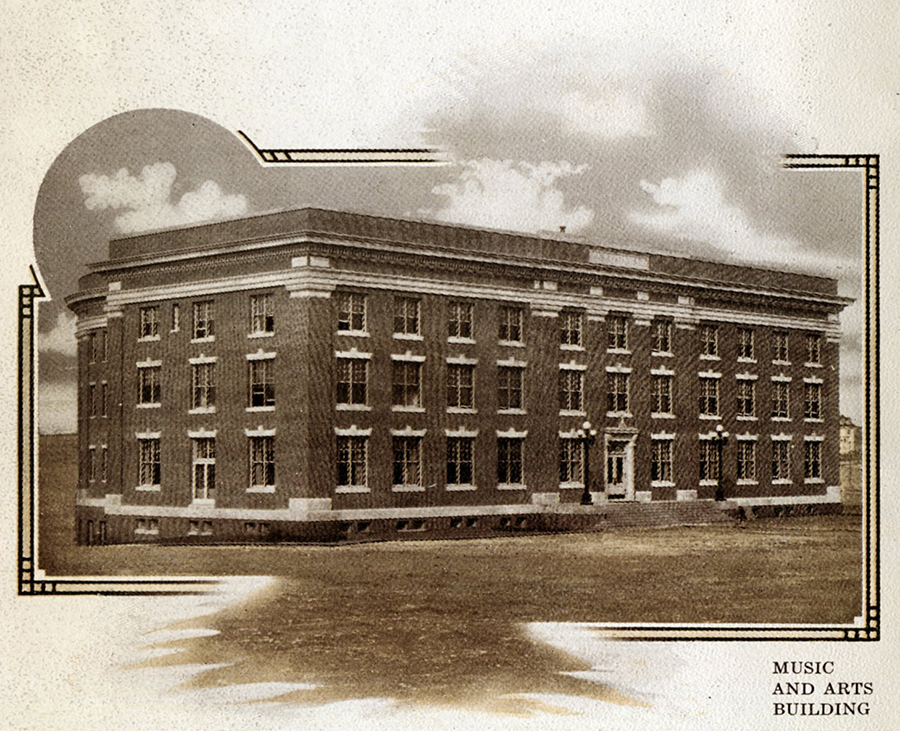

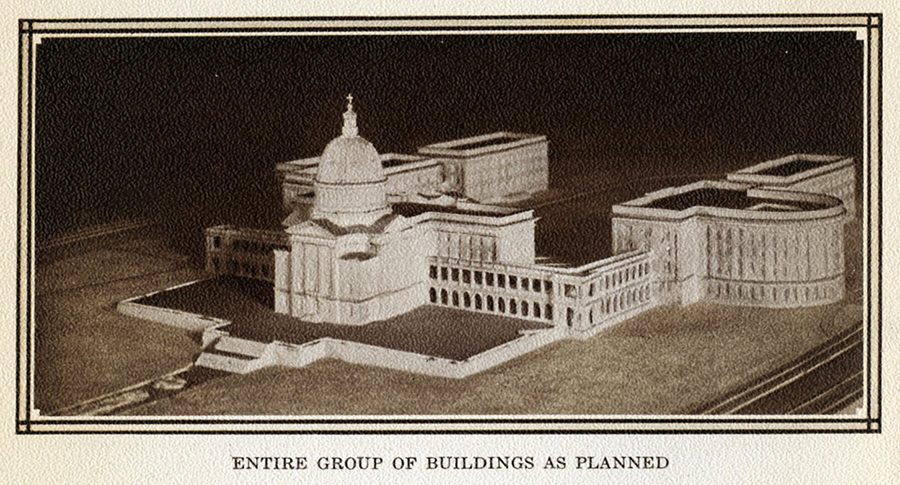

The sisters planned three buildings with the help of architects Messrs. Wilder and Wight and hoped to obtain a $300,000 loan, worth $7 million today. The directors claimed that such a project would result in unfinished grounds, and they denied the request. Once O’Neill adjusted the request to the construction of just one building, the Music & Arts Building, the directors agreed and the sisters signed 600 $500 bonds.

Once built, the school could begin the search for young women. They placed an ad in the “Kansas City Times” before the 1910 school year which promised a “highly restricted neighborhood,” asked for references on family status and advised those interested to come by way of the Country Club Car, which stretched from Westport down past the campus.

Within the next decade, Nichols announced his plans for the Country Club Plaza, a shopping district similar to the Tudor style storefronts established in the Brookside neighborhood. He planned to incorporate Spanish architecture, classical statues and vendors to provide a fine, outdoor shopping experience for Kansas City’s wealthy.

Class of 1982 graduate Michelle Tyrene Johnson recalls visiting the Plaza with her friends, and the different reactions she might get while shopping with either her white or black friends.

“If I’m with the white girls, I’m a safe black child,” Johnson said. “If I’m with other black kids, then ‘what are we up to?’”

Despite the clear divisions that existed in Kansas City when Johnson was attending St. Teresa’s, she says it is not something that was ever talked about in school or at all, but that it was and still is very noticeable.

“You don’t really have to have the details of the racism to experience it,” Johnson said.

Today, Johnson reports for KCUR and has focused on how housing discrimination has affected generational wealth and the wealth gap in Kansas City. She gives the example of two people she reported on, one white and one black, who bought houses in the 1960s. Forty years down the road, there was a $300,000 difference in favor of what the white buyer was able to sell their home for. When she looks at Nichols’s history, she looks for the “human destruction” his discrimination left behind.

“I approached Mr. J.C. Nichols with a proposition to make Wyandotte Street curve west just at our entrance, which was very close to the street. The city agreed to have this done, and in May 1911 deeded us a curved strip of land, its greatest width being ten feet, and curving off gradually to the old street lines.”

This proposition created the circle drive students drive into every morning, but it infringed on Yeoman’s property, and the school paid them $1,025. In turn, the Yeomans deeded this strip of land to the city.

Additionally, Nichols planned for two triangle shaped intersections running on Westover Road, something he often did to preserve “the natural topography’s rugged beauty in its layout,” Schirmer writes. He incorporated winding roads and complex property restrictions, allowing white Kansas Citians to “choose an address of lasting noblesse.”

O’Neill remarked that “the beauty of the outlay attracted truly fine homes to our street.” Today the neighborhood is still marked by a sign on Westover Road behind our first building, M&A, serving as a reminder of the neighborhood J.C. Nichols meticulously planned.

“If you erase that history then you can’t really learn from that [it],” Himes said. “If you really love an institution, you love it even if its past might not be what you want it to be.”