Fighting for a voice: Exploring the New Voices Act

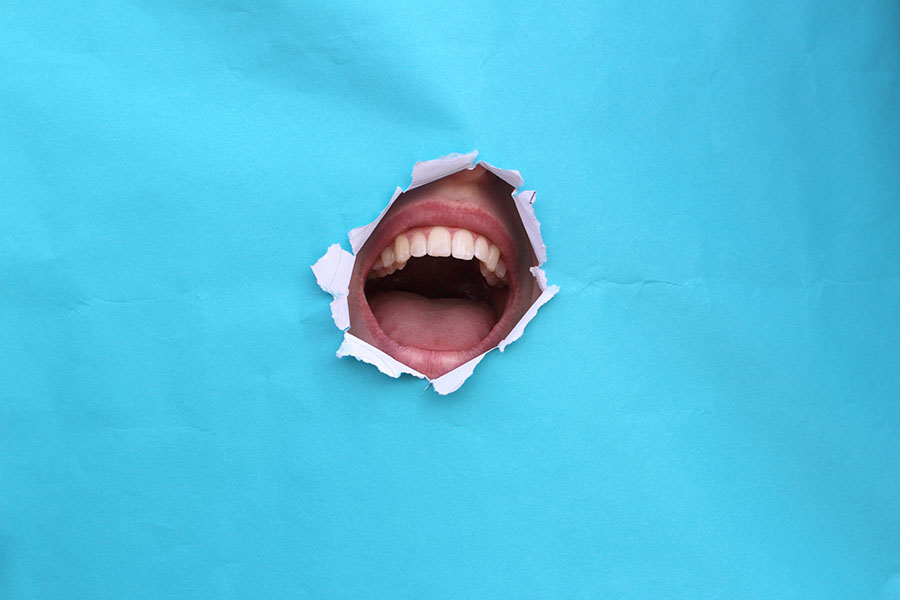

Student journalists facing possible censorship advocate the Missouri New Voices Act—a proposed bill aimed at granting student publications the full protection of the First Amendment.

May 2, 2018

It’s a newspaper nerd’s worst nightmare.

A provocative story is pitched and a dutiful young journalist decides to run with it. Like any good writer, she starts with research. Articles lead to deposition transcripts, contact lists and anything she can find that’s public record. Her eyes are glassed-over, glowing in the glare of the computer screen; they’re stinging with fatigue. It may be Friday night but she’s committed. Entranced, even. She knows this story has to be told.

The turn around is quick and after a week of interviews, drafts and neglected homework, she finally submits her story.

But it’s too controversial. She might create a discussion too scandalous for the community to hear, and that’s too great of a risk. All of her work, time and passion is scrapped.

Teresian co-editor-in-chief Bridget Graham, finds instances of censorship like this to be “heartbreaking.”

“[Student journalists] put so much work into it and no one’s ever going to see it,” Graham said, attempting to explain the emotions at play when a story is pulled.

For Graham, high school publications should be by and for the students.

“In doing that, it has to be true to the students themselves,” Graham said.

She describes a division between the perspectives of students and administrations.

“I do believe there needs to be a line between ‘this is not an advertisement for the school’ [and] ‘this is a message and something written and produced for the students,’” Graham said.

Graham however, acknowledges a persisting stereotype in high school journalism. Stories about drinking and drugs often adorn brightly colored front pages of newspapers, foreshadowing off-color reporting informed by anonymous sources.

“It is tempting to be edgy for edginess’ sake,” Graham said.

But at STA, “most of the time it’s a message,” according to Graham.

Even with more thematic elements, Graham feels that the purpose of the yearbook is to tell the story of the year: the good and the bad.

“It’s just being honest,” Graham said.

In some schools, however, the question of whose story gets told is answered solely by their administration. In Missouri, this question is answered at the state level by the 1988 landmark Supreme Court case, Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier.

Though students from Hazelwood East High School in St. Louis County, Missouri, fought against the censorship of two articles deemed “inappropriate” by their principal, the Supreme Court ruled against them, citing the administration’s “legitimate pedagogical concerns.”

In a 5-3 ruling, the Court reversed the 1969 Tinker v. Des Moines precedent that students in public schools do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

After Hazelwood, student publications at public schools were afforded a lower level of First Amendment protections, except those in states that moved to overturn the ruling with their own laws.

In the four decades since, six states, including Kansas, have passed free expression laws, and in 2015, Jamestown University journalism professor Steven Listopad launched a state-by-state campaign to expand students’ First Amendment rights called the New Voices Movement.

Though the specific bill varies by state, the goal of New Voices is the same everywhere: “to pass anti-censorship legislation that will grant extra protections to student journalists,” according to the campaign’s official website.

So far, advocates have succeeded in enacting anti-Hazelwood legislation in 15 states, and the push for pending legislation continues in New York, New Jersey, Wisconsin, Nebraska and Missouri.

Bob Bergland, a 20-year adviser of Missouri Western State University’s Griffon News, was moved after hearing Listopad speak at the “Walter Cronkite Conference on Media Ethics and Integrity” and was among the first to bring the movement to Missouri.

“If we want our youth to vote, to be civically engaged, to be knowledgeable and passionate members of our society, then we need to have them exercising their rights in high school,” he wrote in an essay for the Grassroots Editor.

“When they are trained not to question authority, when they are trained to be PR hacks and tools of the administration to promote the agenda of those in power, we are not preparing them to be citizens in a democracy.”

Under the leadership of Bergland and sponsorship of Rep. Kevin Corlew, the Walter Cronkite New Voices Act is currently approaching a vote in the Missouri Senate for the third time. Upon each attempt, it has passed easily in the House but never reached a Senate vote — once due to concerns about advisers not being protected and once because of “filibusters and infighting,” Bergland said.

Camille Baker, one of the editors-in-chief of The Kirkwood Call, the student newspaper at Kirkwood High School just outside of St. Louis, testified in January of 2018 and returned March 27 to speak in front of the Senate Education Committee.

“It was intimidating,” Baker said. “But something that is so imperative to do, to stand up.”

During both of her testimonies, Baker worked to highlight the perspective of the high school journalist. In March, though, her message was largely the same save for details about the recent mass shooting in Parkland, Fla. and the young activists it produced.

“When these amazing young activists start speaking out, the platform they use is journalism and they use the voices on their staffs, and the Eagle Eye staff [at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School], I know has done a lot,” Baker said.

The New Voices movement has also lent Baker’s voice to advocacy. In the future, she wants to continue speaking about issues relevant to student journalists.

“I think that people are starting to realize the importance of student journalists and starting to take us seriously,” Baker said.

According to Baker, even though the New Voices Act is a step in the right direction for journalism, advocating for it has been difficult.

Missouri House Bill 441 section 171.200 states that a school district cannot authorize any prior restraint of any school-sponsored media unless it is deemed libelous or slanderous, constitutes an unwarranted invasion of privacy or violates the law.

This list of exceptions has been recently amended to include anything that “so incites students as to create a clear and present danger of the commission of an unlawful act, the violation of school district policy, or the material and substantial disruption of the orderly operation of the school.”

“Well, what does that mean, you know?” Baker said. “You could write a controversial article and it could be disrupting people in class that don’t agree with it. Does that mean it’s unethical?”

For Baker and others, these changes are known as “killer amendments” because of how they weaken the bill. This is the form of opposition New Voices advocates are facing in Missouri.

“There’s just always the old-school people who assume that only libel and slander are going to come from giving this First Amendment power to students,” Baker said, explaining why the bill continues to be “watered down.”

Baker attributes the attempt at weakening the bill to the Missouri School Board Association.

“I know that they have been responsible for demands to change the language of the bill,” Baker said.

Despite the fact that Missouri’s New Voices bill is significantly less powerful than those of Kansas, Iowa and Arkansas, Baker, her adviser and her staff aren’t going to let up.

“Student journalists are going to keep pushing,” Baker said.

However, the New Voices bill only pertains to public university, high school and middle school publications. If approved in the Senate, its blanket of protection would not extend to private schools, especially religiously-affiliated institutions like STA.

Bergland believes adding a provision to cover private schools would hijack the current bill’s chances of passing. But, he says, the New Voices Act could help set a precedent for private schools to follow.

Yet adhering to those laws in a Catholic school would be a risk, according to STA president Nan Bone.

“We’re very willing to work with [the Dart and Teresian] to say ‘If you’re going to write a story that could be questionable, please show both sides of the story,’ because we are a Catholic school,” Bone said. “We follow the mission of the bishop, and so we want to make sure that we’re always following Catholic doctrine.”

Current policies in the STA handbook stipulate that teachers and administrators “reserve the right to decide the appropriateness of any artwork, drama presentation, poem, journalism, or literature for display, publication or performance.”

Because the school is owned and sponsored by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, “any work that is graphic in a sexual or violent manner, that promotes the use of drugs or alcohol, or that is incompatible with the values and philosophy of the school will not be exhibited, published or performed,” the handbook reads.

Bone estimates that when STA publications approach administration with controversial stories, 90 percent of the time they are allowed. The 10 percent that are axed contain content that “would be questionable with Catholic doctrine or with the mission of the Sisters of St. Joseph,” she said.

Bergland believes that in schools with more conservative administrations, student journalists are forced to choose to cover only the minute details of academia: new course offerings, football game scores, award ceremonies.

“For any of those students who want to be journalists, [censorship] kills their passion,” Bergland said. “It kills it. It hurts their education, because they’re not covering the types of stories that they might be covering as a journalist in college and the real world.”

He maintains that the most serious consequence of censorship is that it leads to complacency among student journalists. When their ideas are shot down, students stop thinking that way, preemptively keeping their mouths shut.

“You have this self-censorship going on, and that in some ways, is even more insidious than the censorship itself,” Bergland said.

Brandon Cooper • May 2, 2018 at 6:39 pm

Very informative !!!!!!!!!! I really like this article a alot, keep it up !!!!!!