by Katie Parkinson, photos by Julia Hammond, photo submitted by Sam Matthes

Looking back, in some ways, the morning of Nov. 13 was like any other, according to principal of student affairs Mary Anne Hoecker. She woke up at 5:30 a.m., she took a shower and she washed her hair. She dressed, brushed her teeth and got ready for the day as if it were normal. But it wasn’t. She couldn’t eat breakfast and hadn’t for hours. She was hungry, anxious and waiting.

Then, she got the call.

“We think we can take you in early,” a nurse’s voice on the other end said. So at 9:30 a.m., Hoecker gathered her things, met up with friends Diane Gupta and Sam Matthes, and went to the Indian Creek Campus of the University of Kansas Hospital for her mastectomy.

Shock and fear

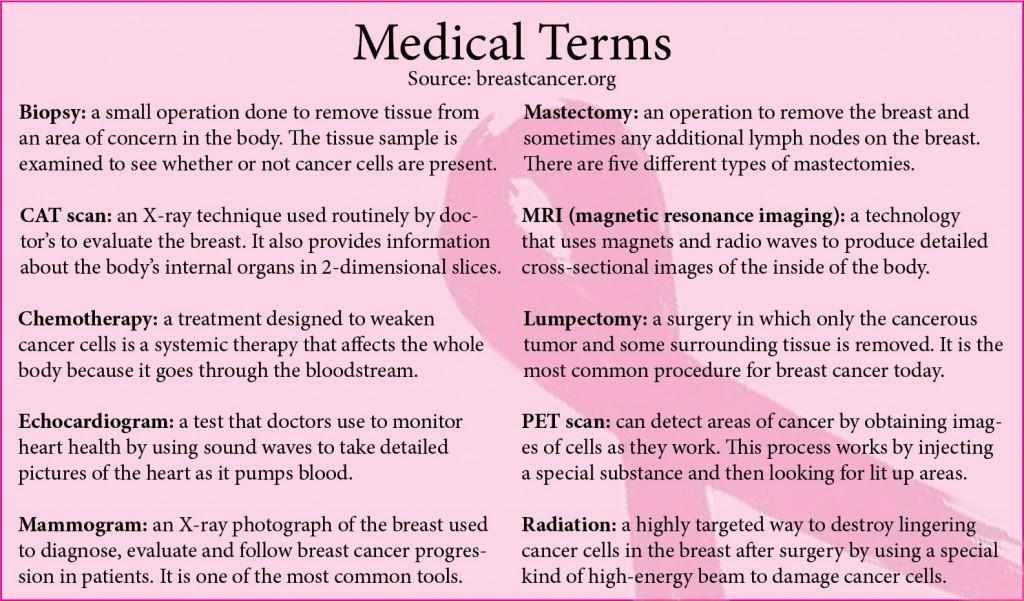

It was October when Hoecker received the diagnosis of breast cancer. The first few weeks were a whirlwind of activity and confusion. She found a lump. She had a mammogram and a sonogram, saw a surgeon, had a biopsy and then an MRI.

“I think mostly I was in shock,” Hoecker said. “I was in shock, and then that night, I didn’t sleep at all because I was also in fear and horror.”

One of the first things she did was ask Matthes (who was there when she had a lumpectomy 11 years ago) to be her advocate and go to doctor’s appointments with her as an extra set of ears and eyes.

“It’s so much to assimilate,” Matthes said. “I don’t care how bright you are, but there’s only so much we can assimilate when we get that kind of news.”

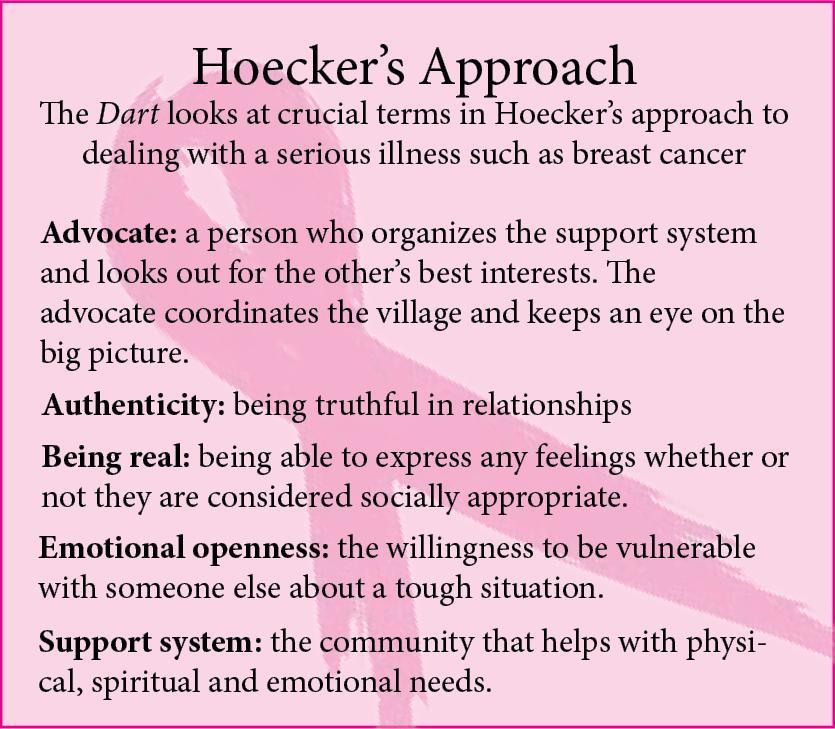

According to Matthes, being an advocate essentially means organizing a support system.

“[Being an advocate is] helping make sure all her physical needs are met,” Matthes said. “It’s making sure there are people there for her spiritual and emotional needs so she can use all of her energy to fight the cancer.”

As an advocate, Matthes has been there from the beginning. She was there when Dr. Ami Jew of KU Med mapped out Hoecker’s treatment options. She was there to “keep it real,” as Hoecker describes it, and in her own words, to “be honest [while] looking out for [Hoecker’s] best interests.”

After Jew mapped out treatment options, Hoecker remembers walking out disbelieving and stunned.

“I’m overwhelmed by this,” Hoecker told Matthes.

“I don’t know what I would do if I was in your shoes,” was Matthes’ reply.

“That is so real,” Hoecker later described of this moment. “That is what I needed. I didn’t need somebody to say, ‘Oh, don’t worry, five months from now you’ll be over it.’ I still felt overwhelmed, but I felt better. Being real about how you feel and having somebody do that for you is great.”

Linked by pink

- Pink cloths that were made by fibers students wrap around trees in the quad as a symbol of breast cancer awareness. photo by Julia Hammond

“When you have a serious disease like this, you need a village,” Matthes said.

While this is often said about raising children, it is not as often applied to having a serious illness, although, according to Matthes, it should be.

When people are confronted with such a serious and scary life-changing prospect as cancer, it can be easier to go into denial, not want to talk to anyone and not want to ask for help.

However, Hoecker found a different way of moving through illness. She found and organized emotional support for herself, which can be a hard thing to do when someone is afraid of the pain and afraid of the fear such an illness can bring. Matthes likened Hoecker’s support system to a construction crew. She is a foreman, and it is her job to make sure the rest of the crew knows what is going on and how they can help – physically, emotionally and spiritually.

According to Hoecker, there has been a network of people who have helped take care of her, prayed for her and supported her during this difficult time.

At STA, the student body dressed in pink to honor her and organized a Pantene Beautiful Lengths hair donation ceremony in her name. Seniors Natalie Rall, Bailey Whitehead, Cecilia Butler and Audrey Muehlebach made a video, inviting students and faculty to say how Hoecker had impacted them or what they loved about her.

“We wanted to, as a student body, say how much we loved and appreciated Ms. Hoecker,” Rall said. “It was a team effort.”

Hoecker responded in an email that the video had “touched [her] heart enormously.”

“I just feel so much love coming from the students, teachers, faculty and friends and the administration,” Hoecker said. “I’m kind of overwhelmed at the response.”

According to Matthes, the video reminded Hoecker of how important the girls at STA are to her.

“You end up having a different value system in some ways,” Matthes said. “You girls are like her kids. She is so committed to you, and I think this has given her a new perspective on her relationship with you.”

While Hoecker has experienced a positive, caring response from her community, according to Matthes, this doesn’t always happen.

“I think one of the things that happens when someone gets sick is that people disappear,” Matthes said. “I think they disappear because they are scared, and I understand that, but it’s probably the most counterproductive thing they can do. I would say that if you’re coming from the heart, there’s nothing wrong you can really say. How can saying, ‘I’m here for you’ be wrong?”

According to Matthes, sometimes people don’t realize how much their presence matters.

“I think the most important thing is that, Mary Anne and the people who are helping her, we can’t get through this without knowing people have our backs,” Matthes said.

Waiting for a mastectomy

As the Nov. 13 date of her mastectomy advanced, Hoecker said, “I don’t want to choose a mastectomy, but I feel I need to. My life is bigger than my breasts. My essence as a person is in my heart and my conscience. It really comes down to, ‘How do I love, and how do I take in love?”

Although she was unsure of the future and facing cancer for the second time, Hoecker was not angry.

“That’s not to say I won’t be mad down the road, but right now, being mad feels like a waste of my time,” Hoecker said. “I feel arrogant to think, ‘Why me?’ I just think it can happen to anybody, and I’m not some exception.”

Still, Hoecker was anxious.

This was exacerbated when circumstances required her to wait at the hospital for her mastectomy over an hour and a half. Sitting in a small cubicle, Hoecker waited with Gupta and Matthes. Doctors and nurses came in and out to ask questions about medications, and Jew marked her left breast. Hoecker had a conversation with one of the anesthesiologists about STA’s track and field facilities and ran into a woman who had attended STA for two years. At times she joked with her friends, saying, “Well, I’m ready to go home now.” At other times she would be real about the situation, admitting that she hated waiting.

“It was just, ‘I can’t believe I’m waiting for a mastectomy,’” Hoecker said. Matthes described the feeling as “sitting on pins and needles.”

“I felt like it was really important to let my mind and my spirit go to a place that felt supportive,” Matthes said. “Otherwise the scare takes you over.”

At 12:30 p.m., Matthes and Gupta left the cubicle for the waiting room, and Jew was ready to begin the mastectomy.

From treatment to treatment

About two hours later, Hoecker regained consciousness. The first thing she remembered was a nurse asking her pain level, which she responded was an eight out of 10. After being given pain medication intravenously, Hoecker was totally relaxed.

“Evidently when I’m under sedation or pain medication, I talk a lot,” Hoecker said. “People told me that I said, ‘I feel great!’ a lot. That was fine by me because I didn’t want to feel any pain.”

During the mastectomy, the doctors had taken one breast and 11 lymph nodes. Of those 11, only one was cancerous.

“I was very relieved,” Hoecker said.

Following this were more tests – a CAT scan, an echocardiogram for her heart, and a PET scan which revealed a few more suspicious lymph nodes.

The doctors told Hoecker that she needed to move into chemotherapy treatments as soon as possible.

Healing through poison

Hoecker had her first chemotherapy session Jan. 2, followed by more sessions, at first in two-week intervals, then one-week increments. By the projected end date in May, she is scheduled to have 16 treatments.

Each time, she goes through a laborious, three-hour process. First, Hoecker checks in and has her weight, temperature and blood pressure taken. A nurse also draws blood so they can check the condition of her platelets.

Then, she is led into a room divided into four “pods,” as they are called. Each pod is occupied with multiple patients, so there is no privacy.

“People are very respectful,” Hoecker said. “They can talk if they want to, but a lot of people were reading, listening to music or sleeping. It was weird to go through it, but the first chemo was very peaceful.”

After Hoecker settles into her pod, a nurse orders the needed medicine for that day so it is fresh. Over the next three hours, Hoecker is given multiple solutions including an anti-nauseous treatment and the chemo itself, which lasts about 45 minutes. Each treatment is held in a bag attached to a movable rack and is administered through a needle that is inserted in a port in the upper chest, just under the collarbone.

“Sitting in a room where a number of people are getting chemo, sitting in these reclining chairs with all these bags hooked up is surreal,” Matthes said. “I felt like I was in an alternate universe.”

For her first treatment, Hoecker came prepared with an iPod loaded with soothing songs from artists such as Yo-Yo Ma, James Taylor, Andrea Bocelli and Barbra Streisand. While she relaxed, Matthes crocheted next to her.

According to Hoecker, the side-effects of chemotherapy are worse than the treatment itself, and she has experienced everything from fatigue and constant nausea to heartburn to hair loss.

“It seems like every day there’s a new [side-effect,]” Hoecker said. “I had one day where I didn’t have anything, and it was wonderful.”

According to Matthes, while she understands that chemo is accepted as one of the best treatment for cancer today, she still believes it is a “dissonant” idea.

“Here are all these people hooked up to machines, putting poison in their veins,” Matthes said. “I think it takes an incredible amount of courage to take the risk of letting somebody put poison in you as a way to possibly heal you.”

According to Hoecker, when a patient is done with all of their chemo treatments, everyone in the room claps for them.

“When I went in for chemo, I told the nurse that I was a first-timer, and the nurse said, ‘You’ll find a lot of warriors in here, and you’ll be one too,’” Hoecker said. “And I thought that was absolutely true.”

Hope for the future

If Hoecker finishes chemotherapy in May, she will continue to visit the doctor to be scanned to make sure there is no sign of cancer, according to Matthes. Then, if her scans keep coming back clean, and the doctors are sure they have gotten all the cancerous cells, she will be declared to be in remission, and a difficult process spanning about eight months will hopefully be over.According to both Hoecker and Matthes, while this is a long, difficult journey, good things can still come out of it.

“I’m not saying it always does, but it can help you take risks in terms of being authentic in a way you might not have before because there’s this feeling of ‘what do I have to lose?’” Matthes said.

According to Hoecker, when she is on the other side of this process and in remission, she hopes to be more conscious and compassionate.

“I want to be open to all there is to learn,” Hoecker said. “I think this is going to help me be more compassionate when other people go through similar things that I’ve not experienced. That is my hope and my prayer. I have a lot of support, and I think I will be very happy.”