story by Jordan Berardi, photos by Julia Hammond, alternative coverage by Lauren Langdon

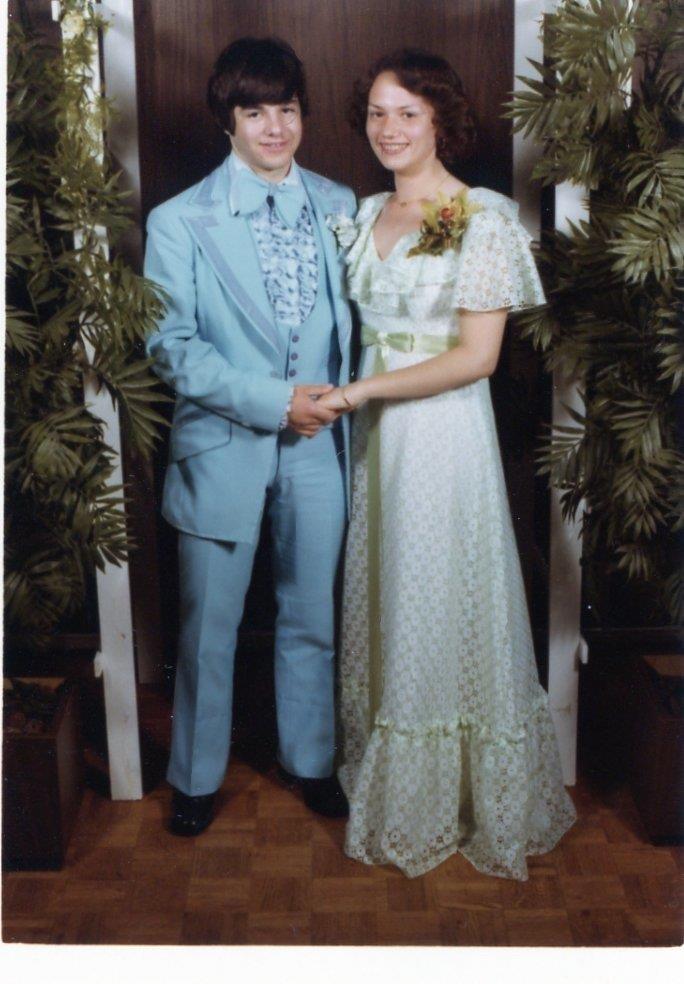

A girl stands at the end of a hallway staring at two wooden doors with no handles. She reaches to her side and her hand meets a button. She presses down. The silence of the hallway vanishes as the doors make a startling racket and begin to open. The girl’s eyes are greeted with bright colors and a reception area. She checks in, gets her photo taken for her visitor pass and walks toward another set of wooden doors. She repeats the door procedure and walks wide-eyed through the doors a second time. Her eyes search the children’s intensive care unit for room 4423. She sees it, second room on the left. Through the sliding glass doors the visitor sees a bright-eyed girl laying in a hospital bed, attached to tubes and machines of various purposes.

[nggallery id=598]

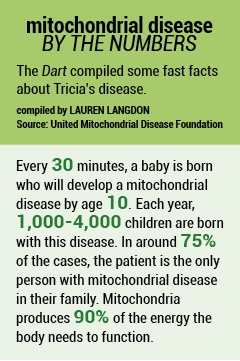

The bright-eyed girl is sophomore Tricia Melland. Melland suffers from a rare form of mitochondrial disease, or “mito.” According to the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation, Mitochondria are present in every cell in the human body except for red blood cells and are responsible for producing nearly all the energy needed to sustain a person’s life. Mitochondrial disease attacks mitochondria, therefore, shutting down whole systems of the body. A person with mitochondrial disease is usually born with the genetic mutation, but the mutation is dormant until it is triggered, either by surgery or a virus. After the mutation is active, a small cold or flu virus can greatly compromise the diseased person’s life.

For Melland, the trigger came at the age of seven when she had a fluid-filled growth called a cyst in her wrist. Usually, cysts are left alone and will die on their own, according to Melland. However, Melland said because the cyst was on her growth plate, a region of tissue that controls bone length and shape, surgery was necessary to remove it. According to Melland, doctors were unaware of the presence of the mitochondrial disease mutation in Melland and used an anesthetic called proposal, which, in those with the mutation, is highly dangerous and is liable to trigger the attacks on that person’s mitochondria. It was after Melland had proposal that her illness became constant.

Following the surgery on her wrist, Melland was often sick. Diseases such as asthma, intestinal failure and anemia, among others, were frequently added to her medical history. At the time, the cause for these illnesses was unknown.

Doctors diagnosed Melland with mitochondrial disease when she was 13. For the Melland family, the diagnosis was a relief more than anything.

“It’s almost a relief to have some sort of idea of what’s going on,” Patrick Melland, Tricia’s father, said

“It’s almost a relief to have some sort of idea of what’s going on,” Patrick Melland, Tricia’s father, said

In August 2010 Tricia caught a flu virus which shut down her GI tract, or her stomach and intestinal tract. Tricia was unable to eat because of her GI tract failure, and a tube was placed inside her nose which went down her throat and into her small intestine. According to Tricia, this tube nourished her with baby formula. This is how Tricia ate and was fed for about a year and a half.

But Tricia got sick again, and this time, the illness shut several more parts of her body down, making it impossible for the tube to feed Tricia. She was then put on IV nutrition, Tricia’s current eating method, which feeds her through a central line in her chest. Using this line comes with serious risks.

“[The central line] comes with risks, life-threatening risks, but [Tricia] has to have it,” Wendy Melland, Tricia’s mother, said.

The line can never get wet and must be bandaged using highly anti-bacterial solutions and dressings each day.

Connected to the central line is a 3-liter bag of fluid which is ultimately Tricia’s food intake. This nutrition system is called TPN, or total parenteral nutrition. Tricia is connected to the bag for 18 hours every day, leaving her six hours without the fluids. However, during those six hours, three of them are spent connected to a different set of IV fluids. Because of this, Tricia has not eaten orally in three years.

“Sitting at the table was hard at first, but I’m used to it,” Tricia said. “I definitely miss eating.”

Though she cannot eat, baking is one of Tricia’s favorite things to do.

“I still like the smell of food,” Tricia said. “And really, everything social revolves around food, so I can’t just not sit down with people while they eat because I’ll miss out on so much.”

Because mitochondrial disease affects the production of energy, Tricia said she is “tired all the time.

“Even though I’m tired, I can’t sleep because [mitochondrial disease] causes so many other issues,” Tricia said. “Like, I have chronic nausea. So I’ll wake up probably two or three times during the night either from nausea or pain, because I have chronic pain too.”

Because Tricia is unable to swallow medicine orally, pain medication is not an option. Instead, she has to accept the pain and “just deal with it.”

In her freshman year at STA, Tricia was in and out of the hospital and was only able to attend two classes a day a few times a week when she was not in the hospital. Tricia said this time was hard on her social life because she was never able to see her friends.

“I really didn’t have much of a social life because I was either sleeping or at appointments,” Tricia said.

Wendy said that she sees the hardship in Tricia missing out on time with her friends.

“[Tricia] should be out having fun with her friends,” Wendy said. “But instead all her life consists of is school and doctors.

But Tricia said this year has been better socially because she has been able to go full days at school, regardless of how exhausting a school day is for her.

“It’s the little things you don’t really think about missing that I miss,” Tricia said. “Like, this year is the first time I’ve ever gone to a pep rally, and I’m in Spirit Club, but I’ve never been to a meeting.”

However, at the beginning of this year, Tricia was admitted to the hospital for two weeks while she underwent several tests and blood transfusions

“Being gone for two and a half weeks is just hard because you’ve missed things that you don’t realize you’ve missed until your friends are talking about it and you don’t know what they’re talking about,” Tricia said.

However, Tricia said she is optimistic when it comes to making it through her sophomore year without any more major hospitalizations.

“I just can’t live in a bubble,” Tricia said. “[When I’m older] I want to be a doctor or a nurse and help kids like me.

Though mitochondrial disease has caused a staggering amount of difficulty in Tricia’s life, she said it has benefited her in some ways.

“I definitely don’t want [mitochondrial disease] but I wouldn’t change that I have it,” Tricia said. “It’s made me stronger and it has made me realize who my true friends are. It has definitely straightened out my priorities and made me appreciate the little things.”

Through her illness, Tricia found her family to be one dominant priority in her life. Her older brother, Bryan, a senior at Rockhurst High School, says he will miss “joking around” with Tricia next year as he heads off to college for one reason

“Because I love her,” Bryan said.

Wendy also said the Mellands’ strong family values have played a part in their strength throughout Tricia’s illness.

“Strong families really pull together [in hardships] and their faith will carry them forward,” Wendy said.

Another overwhelming part of Tricia’s life has been her faith. F.R.O.G., or Fully Rely On God, has been Tricia’s motto since her diagnosis years ago.

“God has played really just a huge part [in my life],” Tricia said. “[Mitochondrial disease] has tested my faith a lot and [mitochondrial disease] has ultimately made [my faith] stronger.”

But the bright-eyed girl is not defined by her disease or the hospital beds which she has occupied, but instead she is defined by the strength and faith she harbors in fighting something that keeps attacking.