A climate for change: environmental education

The Dart examines environmental deterioration on a global, national and local scale, looking to the future for solutions.

March 7, 2016

story by Helen Wheatley and Linden O’Brien-Williams

Writer Stephen Rodrick grew up in Flint, Mich., living with his uncle in a mansion bordering the Flint River. The city had been struggling for years after a long, painful history of the sudden success then sudden failure of General Motors. Once dubbed “Vehicle City,” Flint was a lead producer of carriages and vehicles in the late 1800s. It later became home to GM’s Buick and Chevrolet divisions, notoriously utilizing the Flint River as its dumping ground until the company failed in the 1980s. Rodrick recounts sticking his hand in the water to grab a piece of junk and pulling it out a “mottled, crimson red.”

Until 2014, Flint sourced its water from Lake Michigan, only 70 miles away. In April of 2014, the impoverished city switched its source to the yellow-orange Flint River water in an attempt to save money. Although the state claimed the water was safe for drinking and bathing, GM itself refused to use the water in its plant, claiming it “wasn’t safe to use on car pistons,” according to the Rolling Stone.

Flash forward to 2016 and these effects from the town’s industrial heyday remain. But these effects are not simply present in one city or one state– these are the effects of global environmental deterioration. Since the industrial revolution in the late 1800s, the emission of harmful fossil fuels has taken a great toll on the environment. Flint is one of these stories.

THE ISSUES

In an increasingly industrial world, human action results in the emission of the most destructive gases in our atmosphere. Where humans rely on coal-sourced electricity and petroleum-sourced transportation, the emissions from these activities emit a large portion of the 65% of carbon dioxide comprising the world’s emissions. In addition to relying on these industries, humans also rely on meat production, where poor conditions and mass quantities of animals produce large quantities of methane, a gas that has 25 times higher the effect of carbon dioxide, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA.

The harmful effects, however, do not stop at polluted rivers or smog-ridden cities. Meat production, factories and transportation all contribute to the larger issue of climate change. According to EPA lawyer and STA parent Dave Cozad, various issues have all accumulated to create “the environmental issue of our time.”

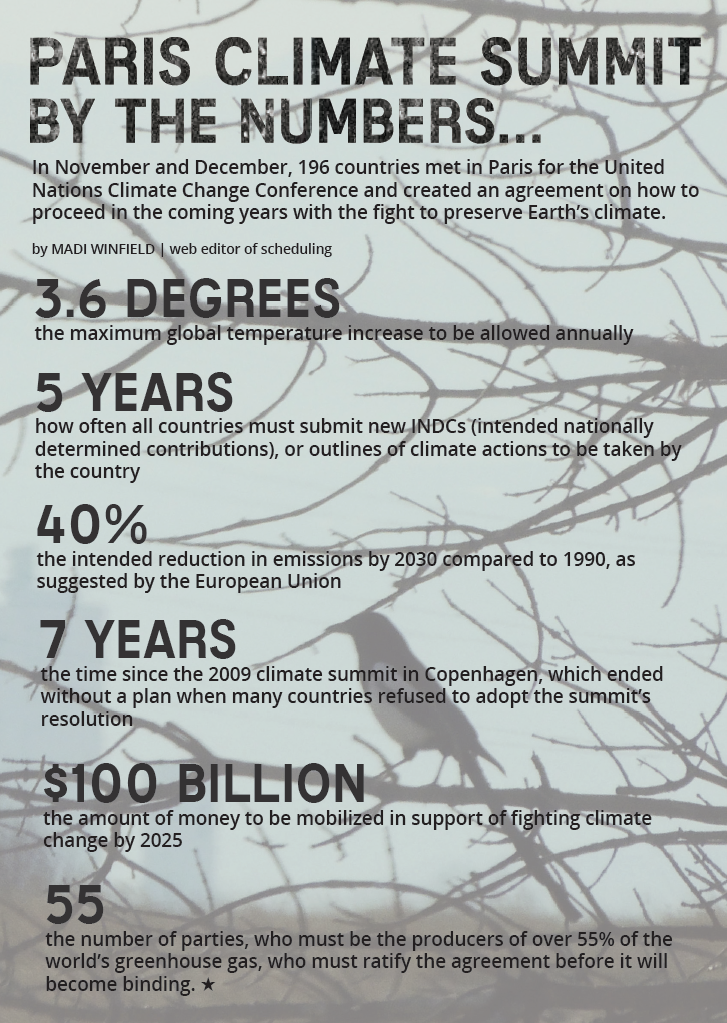

Pope Francis has been one of the loudest voices during these times of conversation and planning. The release of his June 2015 encyclical Laudato Si, or Care for Our Common Home, implores the global community to make radical lifestyle changes. In response to overwhelming outcry for plans to reduce carbon emissions from activist groups and individuals around the world, the United Nations called a meeting to discuss future procedures in Paris, France last November. At the end of the 12 day conference, 196 nations committed to return the earth’s temperature to no more than about 4 degrees above temperatures before the Industrial Revolution. Countries pledged to lower fossil fuel emissions and donate money to underdeveloped areas to help them do the same.

Implementing these changes in the United States has proven difficult with what many are calling a “political gridlock.” Because climate change has become a politically divisive issue, America’s bipartisan system has hindered possibility for change in the country. With a congress composed of mostly Republicans and a Democrat in office, passing laws after the climate talks has become an issue of loyalty to a party. In early February of this year, the Supreme Court delayed President Obama’s plan for cleaner energy until further notice, possibly compromising the United States’ commitments during the climate talks.

The EPA works for change in the country, despite political gridlock, sending the “speedtrap” message that ”if you violate the environmental laws, there are consequences,” according to Cozad.

photos by Maddy Medina

[nggallery id= 1198]

IN KANSAS CITY

While the U.S. has recently attempted to implement beneficial environmental plans, Kansas City has historically been a proponent for these developments. In 2008, the city became an early adopter of climate change plans that would help shape its impact on the living world, according to Kristin Riott, executive director of Bridging the Gap, a local non-profit that initiates environmental change in the community.

“The city itself has actually reduced its own impact about 25 percent since 2005, I believe,” Riott said. “Even though the city has reduced its impacts, the entire region has increased its emissions in that period of time.”

Kansas City has been one of the first cities in the nation to make strides toward creating clean energy, according to Riott, but the future of the town’s climate is uncertain. With projections from leading meteorologists expecting a total of 32 days per summer with temperatures above 100 degrees by mid-century, the city will suffer from the extremes. Kansas City’s tree population, for example, has already been experiencing this change as trees become more susceptible to diseases.

In conjunction with the government, the people of Kansas City, according to Cozad, have contributed to the city’s well-being and awareness with a movement that urges people to relocate “back towards the central city” and use more public transportation. Cozad adds that public transportation is a fundamental piece of sustainability that Kansas City needs to be a cleaner city, but that it lacks simply because of the city’s design.

“[Kansas City] is very spread out and [doesn’t] have good mass transportation, so we have a lot of automobile emissions that lead to climate change,” Cozad said.

In a city with a metropolitan area of nearly 8000 square miles, public transportation systems are widely available, but do not reach every corner of the city. Because of the lack of mass transportation, individual transit becomes the norm and solutions like carpooling or mapping a bus route are not often explored. According to STA science teacher Taylor Scott, who will teach AP Environmental Science next year, inconvenience becomes a major roadblock in reaching sustainability.

“We as humans like convenience of things,” Scott said. “We as consumers have whatever we want or need usually in some kind of reach.”

Inconvenience proves to be a deciding factor in how humans interact with the planet, according to both Scott and Cozad. While people rely on meat, they rarely pause to think about its origins. Likewise, because the majority of Kansas City’s energy comes from coal, Kansas Citians rarely pause to think about how burning coal “is the dirtiest and worst source of electricity for climate change,” according to Cozad.

“When you flick a light switch, where did that come from?” Cozad said. “That light means someone dug it out of the ground and destroyed a mountaintop to burn [the coal], some sulfur dioxide and other chemicals went into the air… Then after they burn it, there is coal ash to dispose of, too…”

alternative coverage by Madi Winfield

[nggallery id=1209]

SUSTAINING A FUTURE

True sustainability means living in a world with what Riott describes as a “closed loop economy”: reusing resources without creating new waste or depleting existing assets. No one has created the perfect plan for a perfect economy of goods, but the EPA has developed three main focuses for creating this utopian consumption: environmental, social and economic. Scott identifies that most people falsely expect the recycling, or economic component of sustainability to be the only piece necessary for the survival of our world.

“The environmental piece is a huge piece of that, but there’s also the education side and the social justice side,” Scott said. “…It’s not only ‘What can I do to reduce my footprint for future generations?’ but it’s ‘can we help those in other countries that don’t have the technology to do that?’”

The economic side of sustainability encompasses the idea that clean practices can actually benefit the economy and provide private businesses incentives in developing a better future. For Riott, progress is imminent not because of change in politics but because “we’ve crossed a very important dividing line” where it’s now cheaper to make energy from renewable resources, a profit motive she believes will speed up the process of sustainability.

The social sphere of sustainability incorporates the future of every person’s role in global preservation. Social sustainability means educating and fostering a sense of community in every individual’s daily life. For EPA lawyers and environmental politicians, science teachers and organic food experts, these are parts of career and passion. Educating others becomes part of the cycle of responsibility found through these pursuits. Scott believes it will be critical to educate the community about these topics in the upcoming years.

“Educating our community and continuing to provide others with basic needs… is that full circle of making sure that future generations will continue to have the resources that they need,” Scott said.

STA’S ROLE

As an institution educating and shaping the lives of young women, St. Teresa’s molds the next generation’s sustainable habits both inside and outside of the learning environment.

In efforts to reduce its carbon footprint, STA’s contemporary Windmoor building uses geothermal wells as a sustainable source of heating and cooling for the building, according to STA’s website. Because the school cites care for the environment as a core value, STA has also mounted solar panels in an effort to reduce yearly electricity fees and carbon dioxide emissions.

To complement the school’s motto of caring for the dear neighbor, STA’s science department will offer a new course that incorporates care for the planet for the 2015-2016 school year. AP Environmental Science will explore the experimental side of environmental science, but will also integrate the other spheres of sustainability in service, sociology and social justice.

Scott’s enthusiasm for the class stems from her belief that topics like environmental science often “fall through the cracks” to favor the more mainstream pre-health science curriculum. AP Environmental Science will draw in more students who “may not feel like science is for them,” while introducing students to the idea of educating the local community.

“STA does such a great job of reaching out to the community [through basic needs donations],” Scott said. “It’s not only about meeting [the community’s] needs, but also about educating them and the future generations that come after them.”

To meet the community’s dietary needs in an environmentally conscious way, STA must engage in what Riott calls eating lower on the food chain. This idea is based on the fact that meat production entails usage of high quantities of other resources. A single pound of meat requires 2000 gallons of water and 15 tons of grain, according to Riott. Add these factors to the methane gas released by the abundance of animals and Riott believes many environmental issues could be solved by eating more plant-based proteins like cottage cheese, nuts and beans.

At STA, this idea is regularly practiced by the school’s lunch provider, the local Bistro Kids, which sources its food organically. According to head chef Scott Brake, Bistro sources all its meat from local farms primarily because meat production on a commercial scale is “often not as healthy” as meat coming from local farms like Campo Lindo Farms or Rainbow Organic farms.Beyond the danger commercial meat production poses to water supply and students’ health, Cozad says that these farms have destructive effects beyond what can be seen.

“There are factory farms all around the midwest where they have 100,000 pigs in a single farm, or 50,000 cattle in a pen or 300,000 chickens in a pen,” Cozad said. “That generates a lot of waste and really isn’t humane treatment for these animals so we have to ask ourselves, ‘Is that even healthy food?’ But, we like our cheap meat… It’s more of a question for society.”

For STA to become truly sustainable, the three spheres of environmental, social and economic sustainability must intersect. This first step has been taken with new courses, solar paneling, Bistro Kids’ organic initiative and an overall sense of responsibility among students. For Scott, educating the community and educating ourselves about current issues incorporates the social aspect of sustainability as well as planning for the future.

“For self awareness, just the political side of it, with the upcoming elections in the next few years, it’s about asking ‘How can I educate myself on the policies and who thinks what about it?” Scott said.

STA administration is working to impose a paperless initiative in the coming years. By equipping each student with a her own Windows Surface Pro tablet, administration hopes to reach the point where paper becomes almost obsolete in education. For many, this initiative means that different learning styles and different teaching styles must be pursued. Senior Grace Girardeau considers herself an advocate for environmental preservation, but believes paper in education can be an important component to learning.

“We don’t have to stop cutting down trees, we just have to be conscious of how much we’re using,” Girardeau said. “Sometimes technology and protecting the environment go hand in hand, but we don’t always have to be making new innovations. Sometimes we have to simplify.”

In her day to day life, junior Emma Kate Callahan is environmentally conscious by avoiding using plastic baggies in her lunch or using her compost pile at home, which she believes more students should do. Callahan says she is often frustrated by the lack of care for the environment at STA and is frustrated that “we already have the technology to know that humans cause many environmental problems out there” but years later, the problems remain unsolved.

Environmental scientists must look to the future to grasp the implications environmental deterioration have on the present day, and Cozad believes that “your generation is very hopeful.” He says that teenagers now “think about these things more than we did” and that the availability of information is promising.

While the current adolescent generation shows promise for attaining sustainability, Cozad admits that the lacking sense of responsibility in adults, who “don’t care because they won’t be here in 20 years” and youth who “lack the mentality” to think far into the future present a roadblock in truly achieving sustainability on a local, regional or global scale. To combat this, Cozad stresses the importance of understanding the true implications of climate change for all generations in all regions of the world.

“[Climate change] has the potential to change your generation’s lives in ways we can’t even imagine, but were not good about thinking 10 or 20 years from now,” Cozad said. “We think about today. And if we’re going to get serious about climate change, we gotta get serious about thinking about 20 years from now.”