Considering consumerism: the roots, consequences and future of the trade

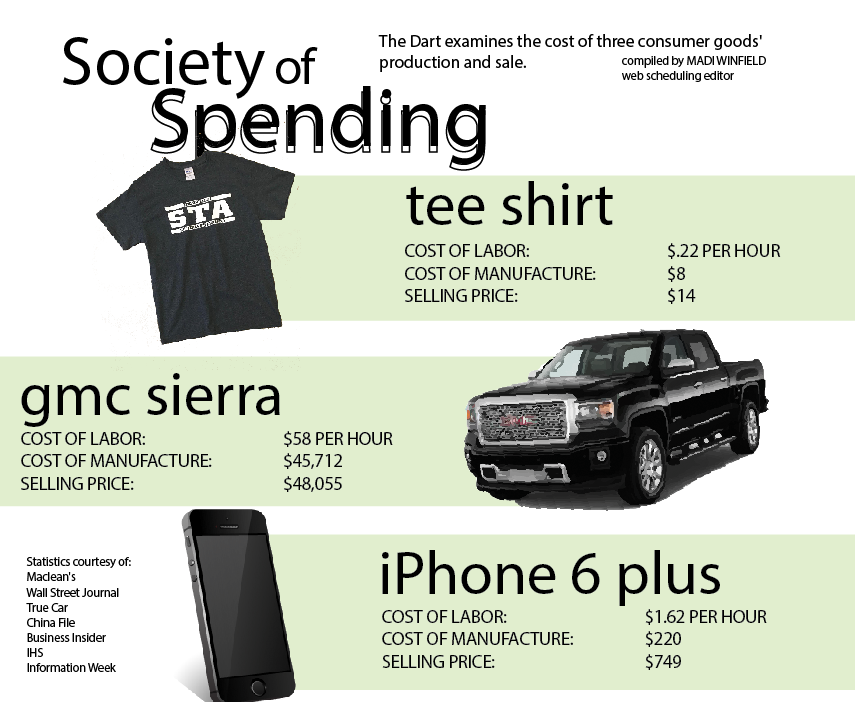

The Dart examines consumerism from its inception as it affects the planet, leaves developing countries poor and creates a culture of disposability in the STA community.

December 8, 2015

story by Helen Wheatley and Jeannie O’Flaherty

For generations, children and adults in the first world have partaken in the constant trade of goods. The Friday after Thanksgiving becomes a feeding ground for the American consumer, and Christmas a season of purchase. Many will tell you we’ve developed a constant need for the bigger, better, brighter, faster and more efficient. But as we dig ourselves deeper into this trade, where does the dark pit finally hit rock bottom? Beyond the iPhone and into the world of poverty and discontent, what is really being traded?

Finding the roots of consumerism

Beginning in the 1950s, consumerism found its footing as thousands returned home from World War II to a newfound eagerness to spend, something many companies recognized and capitalized on. The war had bolstered the economy, allowing Americans to spend more than ever on things like new appliances and furniture, according to a study by PBS.

Senior Maddie Rubalcava sees consumerism as a “societal obsession with goods and produce.” Theology teacher Robert Tonnies believes it is “a culture in which people have a subconscious urge to purchase worldly things.” These two definitions have in common the belief that the issue with the system of consumerism lies in the actions of the buyers. However, by Merriam-Webster’s definition, consumerism is the protection or promotion of the interests of consumers. More simply put, consumerism is the act of making sure buyers get what they want. Why then do individuals assume their actions create the issue? Social Concerns teacher Mike Sanem acknowledges that consumers hold all of the power in this system, but credits advertisers for allowing our “addictive distraction.”

“Advertisers are really smart about branding,” Sanem said. “We all attach symbols of meaning to what we own. Advertisers have figured out really well how to advertise to people who have everything.”

Employee of marketing company Ogilvy and Mather Kat Brown believes overconsumption is an issue in our country, but that advertising “is part of the world we live in” and necessary to keep the economy and jobs alive.

“I think sometimes there can be a negative view of advertising as an industry,” Brown said. “I think people see advertisers as going out there and advertising people things that they don’t need and that’s not good advertising. That’s not advertising in its truest form.”

Brown believes that when a brand or advertiser is working correctly, it’s providing messaging that reaches a certain need in a person’s life.

“I haven’t really come across [selling to people things they don’t need] in my career before, because we are usually looking for a place where there is a need and working to fulfill that need,” Brown said.

Instead of advertising, Rubalcava cites materialism as the driving factor behind consumerism. In the American mindset, she says, materialism is a process– it’s the idea that “the more we have, the more lavish lives we lead.” And for many, a lavish lifestyle becomes so desireable we sacrifice what we can to this “twisted system”, Rubalcava believes.

“No one likes feeling left out,” Rubalcava said, “So we try to compensate for our omnipresent loneliness by filling it with clothes that make us look like we fit the social standard, and pray that we begin to feel it too.”

Eighteen year old Honduran Andrea Bustillo recently moved to the United States when her mother married an American. She finds the root of consumerism in the way Americans value objects.

“The problem starts when we forget the value of the things,” Bustillo said. “We lose the sense of what is an object. We start to belong to the object instead of the object belonging to us.”

Bustillo also finds that the tendency to partake in this culture comes from a lack of attention paid to the consequences. She says that the way people approach the use of their possessions in the nations of America and Honduras is very different.

“We’re not consumerists in Honduras,” Bustillo said. “We don’t have enough money to be consumers. We have a different mentality: when you buy something, you use it to the point where it breaks, or it’s useless, and even then you give it to another person. The last thing you would do is throw it away.”

While advertising and materialism may pull consumers towards a good or product, this mere attraction has not been enough to keep customers returning regularly. In order to support a growing economy, America’s gross domestic product (GDP) must always be growing. Thus, people must constantly be buying new items in order to sustain the steady incline of our economy.

Out of this idea came planned obsolescence: a manufacturing decision made by a company to make consumer products in such a way that they become out-of-date or useless within a known period of time, according to The Economist. The average purchase lasts six months before it stops being used or is thrown away.

“Interiorly, nobody wants to be wasteful, but we have been distanced from where our waste ends up,” Tonnies said. “We are encouraged to move from one interest to another at a rate that is literally hurting our attention spans.”

Brown, who works in advertising specifically for luxury brands, doesn’t come across the idea of planned obsolescence in her work, she says.

“[My company] is investing in brands that really stand behind what they believe in, and you won’t see practices like that happening,” Brown said. “There is a degree to which advertising sets trends and … I think it’s important for advertisers to think about what they’re putting out there.”

For Sanem, the idea of a disposable culture encompasses the entire system of consumerism: the goods being traded and the people involved in their production.

“What if you start throwing away the people who make [the goods]?” Sanem said. “How do you decide which humans are worthy and which can be thrown away?”

Consumerism at STA

For students of St. Teresa’s Academy, consumerism is present because of its prevalence in teen culture and society. From an education standpoint, many institutions like STA are continuing to value the importance of staying current with technology.

“The student experience is becoming more important in education and part of the experience is supplying [students] with things they’re used to from corporations,” Sanem said. “Education itself is an industry.”

Sanem believes the level of consumer awareness at STA is “so obvious.” Rubalcava states that this awareness is often downplayed because of things like uniforms and lack of makeup worn by students, but that it flares up when outside influences are introduced.

“I think a lot of people like to pretend STA is special because we aren’t very materialistic… but when Teresian or Prom rolls around, all you ever hear is, ‘What dress are you wearing?’ ‘Where are you going for dinner?’ ‘OMG post those pics on Instagram,’” Rubalcava said. “We complain incessantly about how slow the netbooks are, or how upsettingly slow the internet is, but in reality we are extremely lucky to have laptops.”

Sanem finds that the symbols of consumerism as STA, like headbands and cars, are often present because of choice by students. But when it comes to things like technology, he believes it’s “hard and expensive” to purchase ethically made products. Tonnies comments on the STA community’s issues as a whole.

photos by Violet Cowdin and Maggie Knox

[nggallery id = 1161]

“We all see [consumerist tendencies] in every person,” Tonnies said. “Nobody is above it. As a school community we could be more conscientious about whether or not certain school functions are encouraging ecological consciousness. We could probably all do better. Catholic Social Teaching demands that we do better.”

If you can’t fight the system, then work the system, and one way to work the system of consumerism is to become aware of your own inner tendencies.

— theology teacher Michael Sanem

Consequences of consumerism

For Americans and laborers alike, the system of consumerism rarely gratifies. The world of trade, as Sanem describes it, is a wide spectrum with consumerism as a distraction on one end and consumerism as the degradation of the world on the other.

During the inception of the idea in the 50s, America’s national happiness peaked and has been dropping ever since, according to The Harvard Business Review. Sanem believes wealth and accumulation of goods beyond a certain extent makes one less happy than otherwise.

“Ultimately, if you’re empty, you’re just going to keep consuming things because you’re empty, and you’re going to feel more and more empty the more you consume,” Sanem said. “[Advertisers] create new needs, and you’re basically prescribing your happiness to something that can’t make you happy.”

Rubalcava finds that materials act as a separation in society and create distance between humans.

“Happiness is something that only comes through being present for the human moment,” Rubalcava said. “As we grow more concerned with monetary and proprietary gain, we become less concerned on how we spend those moments.”

Aside from affecting American hap piness, consumerism plays a role in the livelihood of underdeveloped nations. Many companies have capitalized on their ability to use sweatshops in developing countries for cheap labor that increases profit at home. Nike is one of the most famous examples, brought to light in 2000 through the Behind the Swoosh documentary.

piness, consumerism plays a role in the livelihood of underdeveloped nations. Many companies have capitalized on their ability to use sweatshops in developing countries for cheap labor that increases profit at home. Nike is one of the most famous examples, brought to light in 2000 through the Behind the Swoosh documentary.

For the foreign laborer, first world consumerism is one of the only things he/she can depend on for a steady income– an income that, for 896 million people worldwide, is below $1.90 a day, according to The World Bank. If laborers depend on this wage to survive, what’s the harm done by making goods cheaply in developing countries?

Sanem says our dependence on these goods gratifies a weak central government for developing nations. He believes the only way to allow huge corporations to pay these workers so little is for the peoples in these nations to desperately need the small wage they would earn. Thus, because of their reliance on the wage, it’s in the favor of the consumer and the corporation for these small nations to remain unstable.

“If you go out and buy these things does that mean you’re supporting terrorism?” Sanem said. “No, but it means that to serve the needs of countries that can have the most, you want Indonesia to have a weak central government so that you can pay your workers less.”

Honduras is the top producer of coffee in Central America, but Bustillo says this production rate causes suffering among people of the country.

“You just see the beautiful [product] in the commercial, but you don’t know that people have suffered in the making of those things,” Bustillo said. “People have to realize what is happening not only in their country, but in other countries.”

The effects of consumerism don’t die out with each generation of the poor. The goods we create and throw away every six months leave a permanent impact on the planet. If every person were to consume the way the average American does, we would need four more earths to supply enough materials, according to The BBC.

“We’re going to start seeing the effects of climate change and it’s going to be in lesser developed countries,” Sanem said.

Not only will those already suffering suffer more, those of us in developed countries will eventually see the impact of our actions.

“There’s an environmental problem that will put our very existence at stake,” Tonnies said, “and then we will wake up.”

The poor are more at risk when it comes to the negative effects of climate change, according to The Economist. Bustillo knows firsthand the effects consumerism has on the land and people of poor countries.

“One company was paying nearly nothing to its workers, and using really bad things for the environment,” Bustillo said. “It was so bad that the people who were working there had children with birth defects.”

The future of consumerism

In a world where consumerism is an institution fixed into our social structure, change is very acute if it occurs. Where our economy depends on the idea of continual consumption, the power for change lies in the hands of the consumer.

“We’ve seen companies rise and fall based on the American consumer,” Sanem said. “And that’s the good news– that this is a people-powered system. If we want to change parts of that system, it has to be people powered.”

Bustillo believes change will only start to begin when the individual looks at what purpose goods actually serve in the consumer’s life.

“Something important that we don’t realize is if you buy a watch that is $300, you see the same time as you would on a watch that is $10,” Bustillo said.

For Tonnies, change can only come if individuals convert their own minds and thought processes.

“It’s learning where real happiness comes from,” Tonnies said. “If you personally learn that, you can build your life out from there. We need to transform people’s minds and hearts, and the system will fix itself. ”

Sanem, Bustillo and Tonnies agree that for one person to end consumerism is impossible, and that the process is a slow one. The three share one main idea: individual change creates systemic change. Sanem says that something “magical” happens when people cultivate their inner values and put them into action.

“If you can’t fight the system, then work the system, and one way to work the system of consumerism is to become aware of your own inner tendencies,” Sanem said. “But you can choose your values through what you spend money on. You can vote with your dollar. When people start demanding it, companies will start making it. Let’s put pressure on companies to produce more ethically… If everybody chose a middle ground, then you would see huge changes. If you did a little bit of something you’d have massive change.”