Rise in homeless youths increases demand for help

After years in foster care or makeshift homes, youths build their futures using local services.

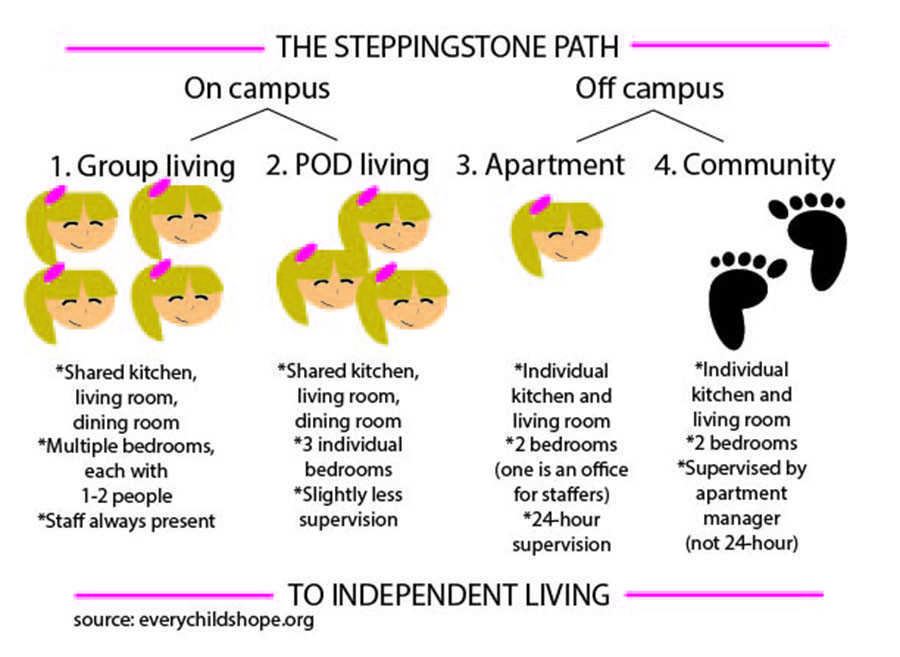

Raytown transitional living program Steppingstone aims to move adolescents from on-campus housing to community apartments.

February 14, 2015

story and alternative coverage by Emma Willibey

Last summer, senior Jessica Favrow volunteered at an open house for Sheffield Place, an agency providing residential services to homeless women and their children. A staff member had asked Favrow and a resident to prepare a salad using vegetables from the garden. As Favrow and the resident cut vegetables, they started laughing. Neither girl could recognize the vegetables, much less know the methods for preparing them.

“We were, like, lost together with what we were doing,” Favrow said.

According to Favrow, the woman revealed no signs of “a rough life.” She was a Sheffield Place resident and Favrow was a volunteer, but both responded to the situation identically. Through Sheffield Place, Favrow said she realized the unpredictability of homelessness.

“Stuff happens,” Favrow said. “[But], if you’re willing to accept the helping hand, then you can find [help].”

According to a report published by the National Center on Family Homelessness last November, nationwide youth homelessness has peaked in recent years, with one in 30 children homeless. In addition, data from the University of Missouri Institute of Public Policy shows increases in Jackson County’s homeless youth population. For the 2008-09 school year, about 2,000 homeless teens attended public school in Jackson County; for the 2012-13 school year, this number nearly doubled.

“Some of [the rise is] tied to the economy,” Lynn Durbin, director of Steppingstone, a transitional living program for homeless adolescents, said. “[The late-2000s ‘Great Recession’] put more stress on families and communities.”

Similar trends have occurred outside the urban core. According to the University of Missouri’s data, the number of homeless youth in Johnson County also doubled from 576 in 2008-09 to 1,240 in 2012-13. According to Leigh Anne Neal, associate superintendent for communications for the Shawnee Mission School District, 349 of the district’s estimated 27,509 students “lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence,” which the McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Assistance Act defines as “homeless.”

Seventy-two of these 349 students are “unaccompanied youth” who not only lack a fixed residence, but also are not in a parent or guardian’s custody. In the Shawnee Mission School District, this involves circumstances such as deportation or incarceration affecting one or both parents.

In such cases, a youth may enter foster care, which transfers individuals from unsafe homes into licensed homes or facilities. Between 2012 and 2013, the number of homeless youths in Jackson County aging out of foster care rose from 36 to 70, as the University of Missouri’s data shows. Missouri’s foster-care children “age out” at 21 years old, and more youths leaving state custody has fueled more reliance on Steppingstone, Durbin said.

“[The rise in youths aging out of foster care] gives us more referrals [from the state] and more demand for services as [youths are] trying to move into independent living,” Durbin said.

While half of Steppingstone’s residents arrive by state referral, the other half are runaways, Durbin said. An intake helps these individuals obtain the essential documents, like birth certificate and social security card, to enter Steppingstone. However, costliness limits Steppingstone’s acceptance of private referrals.

“There is a waiting list,” Durbin said. “We have the capacity to make as many state-custody kids as we can because the state gives us money [to provide services for these kids]. Private referrals you have to pay for on your own.”

Once admitted to Steppingstone, whose housing includes two on-campus buildings in Raytown and two nearby apartments, youths define their educational or career-oriented goals. From attending community college to learning a certain trade, these goals dictate the adolescents’ lifestyles, Durbin said.

“They send out a lot of applications, as many as 15 in a week,” Durbin said. “We expect them to get a job within the first few weeks they’re out of Steppingstone.”

According to Durbin, the adolescents’ individualized priorities lead to individualized schedules, with some youths working during afternoon shifts, others performing overnight shifts and others attending high school. Between these periods, each adolescent learns independent-living skills from a case manager or another staffer.

“Maybe over dinner the staff person will tell [the adolescent] what is going to be prepared for dinner; they may teach [the adolescent] a particular recipe,” Durbin said. “Or, [the staff person] may sit down with [the adolescent] and help them fill out some job applications [or] set up a checking account.”

According to Durbin, such activities are necessary to those shuffled between foster homes for years.

“[Homeless adolescents] don’t want adults telling them what to do,” Durbin said. “So what we do is we allow them, empower them to make their own decisions. In many cases, they haven’t had the opportunity to make their own decisions.”

In the Shawnee Mission School District, the resolution to challenge homeless students also prevails. According to Neal, the district waives school fees for these youths, also offering night classes, online classes and summer classes to encourage graduation. In addition, the district assists college-bound students with the Free Application for Student Financial Aid (FAFSA).

Above all, these services allow homeless youths to feel secure in their futures, Durbin said.

“No kid wants to be in the custody of the state,” Durbin said. “They don’t want to be the kid at school that has the social worker come into their parent-teacher conferences. They want some normalcy and some stability.”

However, those who have endured trauma cannot enjoy independence without accepting the responsibilities, Favrow said.

“Sheffield Place only has so much space,” Favrow said. “You have to be willing to accept [the guidelines].”